Outgrowing Your DIY eCommerce Platform: Modern Migration Paths

Written by

Broadleaf Commerce

Published on

Dec 18, 2025

For a long time, building your own commerce platform felt like the most reliable way to stay in control. Vendors moved slowly. Features you needed did not exist anywhere. And your team understood the business well enough to design solutions that fit your exact workflows.

Many enterprise organizations took that route. It was the right choice for the problems they faced at the time, but business complexity typically creates an IT mess over time. The problem is exacerbated when legacy systems are leveraged in modern solutions, such as GenAI tasks.

And whether your organization is using it or not, AI is already reshaping how product discovery, personalization, and operations function across digital commerce. Internally built platforms that once felt liberating now feel increasingly strained.

Here's why internal systems often reach a natural limit, what pressures create that limit, and how modern commerce teams are approaching migrations today.

1. Complexity grows faster than the original architecture expected

Most in-house platforms begin their lives as tightly scoped systems. The early versions handle a manageable number of workflows and are built around a specific business model. New needs emerge over the years. Additional teams rely on the platform. Entirely new channels and programs get layered on top.

These changes accumulate gradually. At some point, small updates require disproportionate analysis because older assumptions no longer hold. Day-to-day work starts feeling more constrained than it used to, even though the platform still functions.

The issue is not engineering talent. Internal systems naturally absorb the history of the organization, along with every shortcut, exception, and quick fix introduced along the way. The issue is technical debt that accumulates over time.

When companies build internally, they tend to add capabilities as needs arise. Product data might live in several systems. Pricing logic might have multiple sources. Order data can vary by channel. Customer information often takes different shapes depending on the application that collected it.

None of this seems problematic at first, but fragmentation eventually affects everything that relies on data consistency.

Personalization remains shallow because customer identity is rarely unified. Inventory accuracy becomes difficult to guarantee. Forecasting depends on manual reconciliation. AI pilots stall because the data feeding them is incomplete or structured inconsistently.

Eventually, teams find themselves spending more hours reconciling systems than actually using them when data normalization is ignored.

3. Maintenance absorbs engineering capacity

Internally developed platforms demand constant attention: fixing bugs, handling scaling events, patching security issues, maintaining infrastructure, and refactoring older code. The same team responsible for innovation must also keep the system stable.

The result is a persistent bottleneck. Leadership has ideas for new features, programs, and revenue streams, but upkeep cannot be ignored. Even highly capable teams find that the majority of their time gets pulled toward maintaining the foundation rather than shaping the future.

Most organizations reach a point where they could build almost anything, but their ability to build everything their business wants is limited by the hours available. When you’re stuck in maintenance mode, software developers “toil,” working on manual, repetitive and tactical work which keeps them from spending time on more strategic, innovative projects that they want to work on (and you want them to work on).

4. Knowledge becomes concentrated in a small group

As an internal platform matures, a handful of engineers often become the primary stewards of its architecture. They understand how the early design evolved, where complexity sits, and why certain decisions were made. When those engineers shift roles or leave, the team loses far more than documented code.

New contributors take longer to ramp up. Routine updates feel riskier. Caution replaces confidence. Even when the technology still performs well, the organization may realize that it cannot maintain the platform at the same pace without the people who carry its history.

Without clearly documented code, systems and processes, tribal knowledge becomes a real problem, especially as people who have (and don’t share) their knowledge leave an organization.

5. Operational demands surpass the original design

Commerce today is as much an operational challenge as it is a digital one. Real-time inventory visibility, multi-node fulfillment, split shipments, store-based pickup, curbside processes, dynamic delivery promises, and returns management all add layers of complexity.

Many internal platforms were never meant to orchestrate this much operational nuance. They were built for a simpler environment. As the business adopts new channels or accelerates in-store fulfillment, homegrown order routing logic or inventory models often struggle to keep up.

Teams find themselves caught between maintaining stability and modernizing core operational flows. Proper Orchestration, the coordination and management of multiple computer systems, applications, and/or services, stringing together multiple tasks in order to execute a larger workflow or process, becomes a priority with higher urgency as systems grow.

What Migration Looks Like in 2026

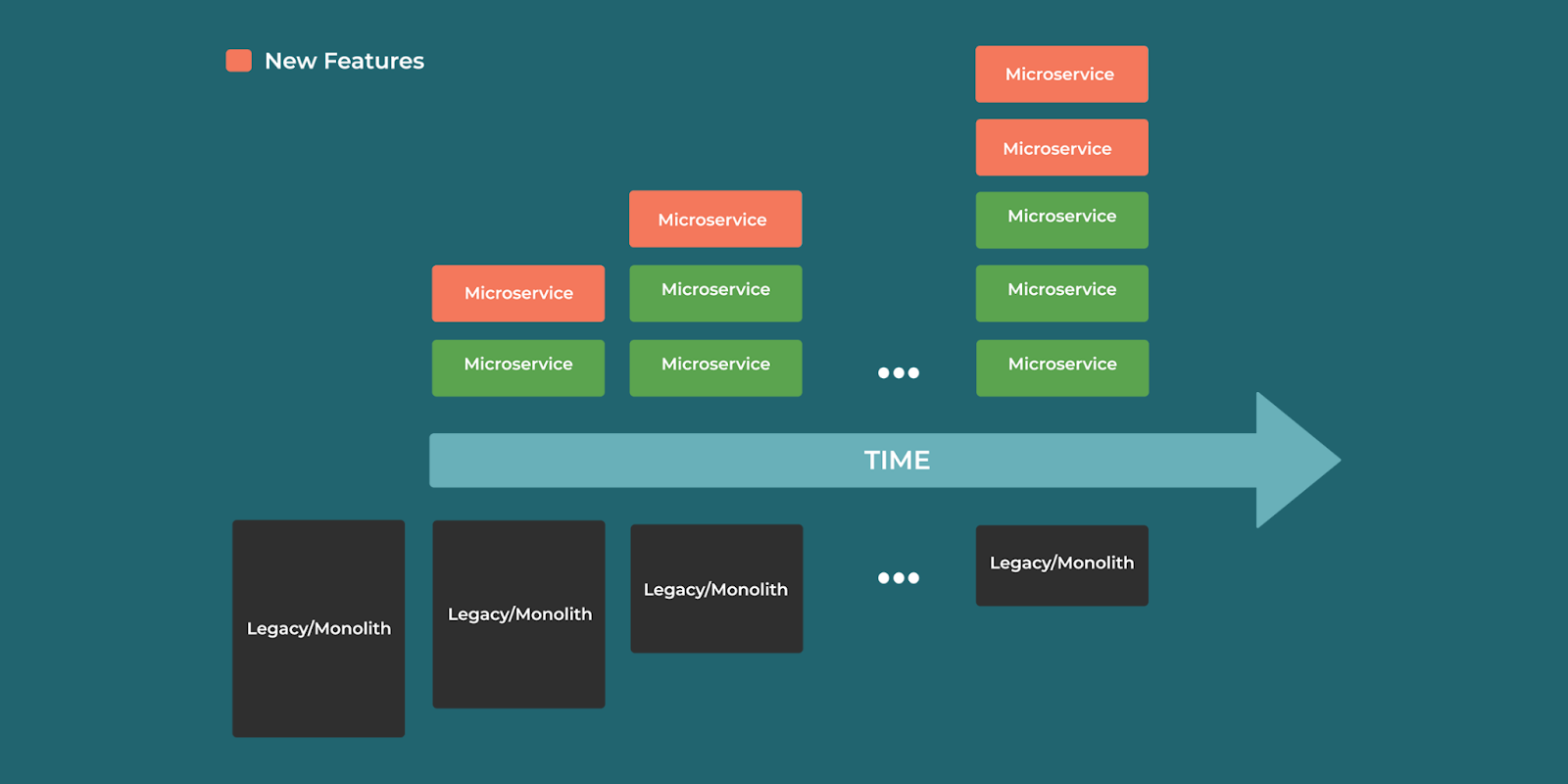

Modern migrations are no longer an all-or-nothing decision. Teams are avoiding both extremes, from rigid, monolithic vendor suites that impose their own constraints to fully composable architectures that fully replace legacy solutions.

A growing number of businesses are choosing platforms that provide a composable solution that allows (and licenses) for the iterative replacement of complex legacy solutions, with clear extension points and a predictable way to evolve.

These platforms allow teams to keep the flexibility they value, while reducing the maintenance overhead that comes from owning an entire commerce engine internally. They also provide a data foundation structured in a way that supports AI, advanced operational logic, and multiple business models under one roof.

Where Broadleaf Fits

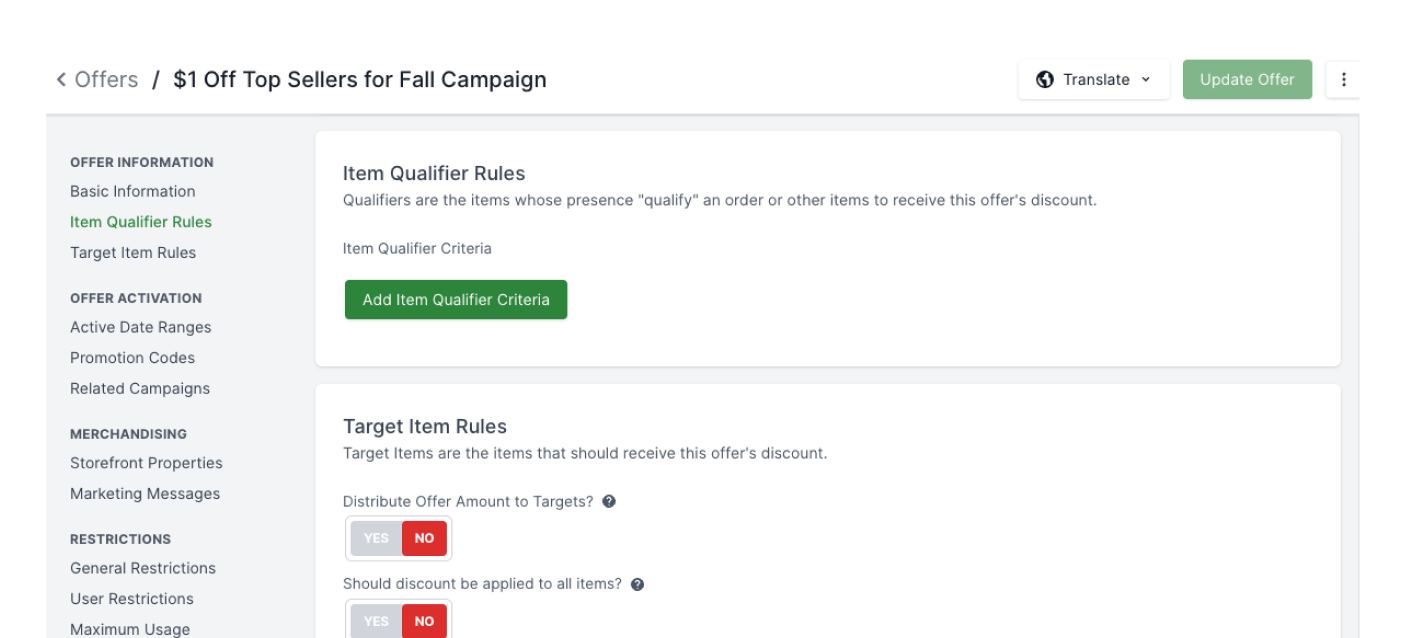

Broadleaf is one of the platforms aligned to this modern composable path. It offers a fully composable solution, licensed by components used, while still allowing deep customization when needed. A single architecture supports both B2C and B2B (not to mention B2B2X) models, which reduces the drift that often appears when organizations maintain multiple systems.

Broadleaf's value comes from reducing the weight of foundational maintenance work, while giving teams the room to focus on the areas where differentiation matters. It is not meant to replace everything an organization has built internally. It is a way to iteratively modernize and accelerate innovation.

A Natural Inflection Point

Teams that built their own platforms did so for good reasons. Those systems often carried the organization for years, but commerce now moves differently. The demands placed on platforms have grown in ways internal systems were never designed to handle at scale.

Reevaluating a custom-built platform does not mean the original decision was wrong. It simply reflects new realities.

Building your own platform was once the best way to stay in control. Today, control looks different. It means having a foundation that evolves with the business instead of dragging behind it. It means freeing your team to work on what differentiates you, not what merely keeps the lights on.

When the platform that once felt liberating starts to feel like a constraint, it's worth asking what control actually requires now.