You Built It. Now Pay Up. The Brutal Truth About Software Maintenance Costs.

Written by

Brad Buhl

Published on

Jan 06, 2026

Your custom software project finally launched on Tuesday, and the steering committee is celebrating. The dev team of ten superstars is already eyeing their next project.

Everyone thinks the hard part is over.

As someone who has lived through enough deployments to have permanent gray hairs, let me be the one to ruin the party: You haven't finished paying for this thing yet. You've barely started.

There is a massive, expensive disconnect between what executives think happens after launch and the cold reality of keeping code alive. If you don't budget for that reality now, that shiny new platform will be a nightmare of technical debt in 24 months.

Here is the golden rule of custom software, backed by decades of painful industry data.

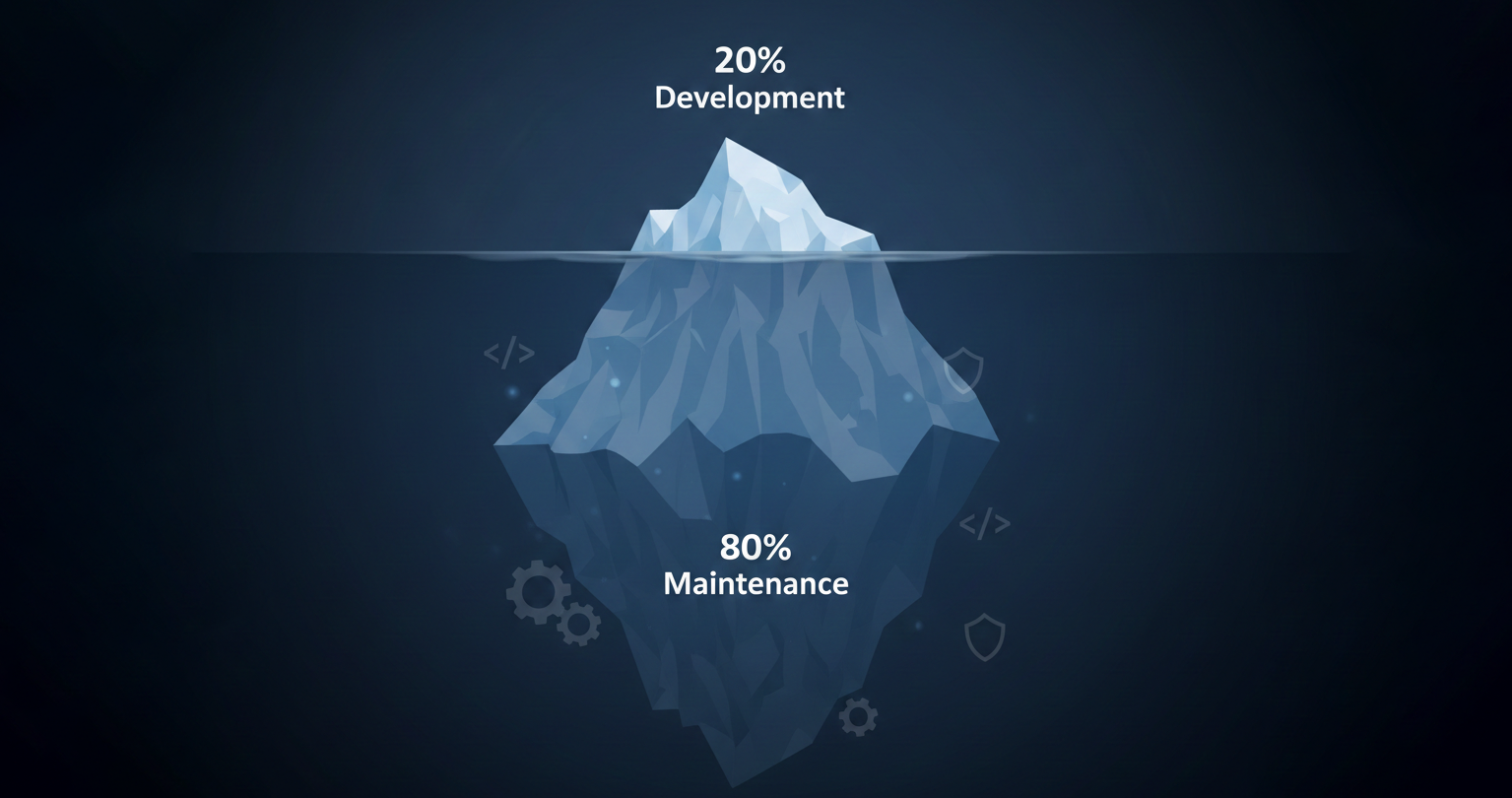

The "20% Rule" (Or: Why You Can't Fire the Dev Team)

Look at the team that built your software. Let's say it took a solid staff of 10 developers, QA, and architects a year to build version 1.0.

You are probably planning to reallocate all 10 of them next month. Don't.

The industry baseline standard, the absolute minimum for a healthy system, is that you need 20% of that original effort dedicated exclusively to maintenance every single year.

If it took 10 people to build it, you need to keep two full-time staff just to keep the lights on. If the build costs $1 million, you need to set aside $200,000 annually, forever.

If that sounds high to you, it's because you misunderstand what "maintenance" is.

Maintenance Isn't Just Fixing Typos

When I tell a CFO they need two full-time staff for an app that's already "done," they assume I'm padding my headcount. "Why do we need staff if there aren't any bugs?"

Fixing bugs is maybe 20% of maintenance work. The other 80% is desperately trying to keep the software from rotting.

Software doesn't exist in a vacuum. It lives in an ecosystem that is constantly shifting under its feet.

Adaptive Maintenance: AWS changed an API, Chrome updated its security protocols, or iOS released a new version that breaks your mobile view. The software works fine, but the world changed around it. You need staff to adapt it.

Perfective Maintenance: Users start complaining that the dashboard is slow when they load 5,000 records. Nothing is broken, but it needs optimization.

Preventive Maintenance: Updating old libraries so you don't end up on the front page of the Wall Street Journal because of a security breach.

If you don't have those two people dedicated to this, you are making a conscious choice to let your investment degrade.

The Industry Research Behind the 20% Rule

Whenever I drop the "20% Rule" in a budget meeting, I get skeptical looks. Don't listen to me then. Listen to the biggest analyst firms on the planet, who have been tracking this data for decades. They all say the same thing.

Gartner: The "Keeping the Lights On" Reality

Gartner has famously tracked IT spending buckets. They consistently find that organizations spend a staggering 55% to 80% of their total IT budgets just on "Run" activities, maintaining what they already have, leaving precious little for new innovation. You can read summaries of this benchmark data over at Idea Link.

IBM: The Lifecycle Truth

IBM knows a thing or two about long-term software commitments. Their research into the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) shows that the initial build is actually the cheap part. The cost of fixing errors in the maintenance phase is up to 100 times more than during design. (Noted in Celerity's review of the IBM research).

The Standish Group: The Scary Math

The Standish Group's "CHAOS Report" is basically the bible of IT project failure analysis. They have perhaps the most sobering statistic of all. Their historical data suggests that for every $1 you spend building software, you will spend $3 to $4 maintaining it over its useful life. (See their analysis on project outcomes in this archived report pdf).

The Bottom Line

Custom software isn't a bridge you build once, cut a ribbon, and walk away from for fifty years. It's a living thing that needs constant feeding and care.

Suppose you built it with 10 people, and budget for those two maintainers immediately. If you don't, you aren't saving money. You're just taking out a high-interest loan called "Technical Debt," and the bill always comes due eventually, usually in the form of a massive, agonizing rewrite five years from now.

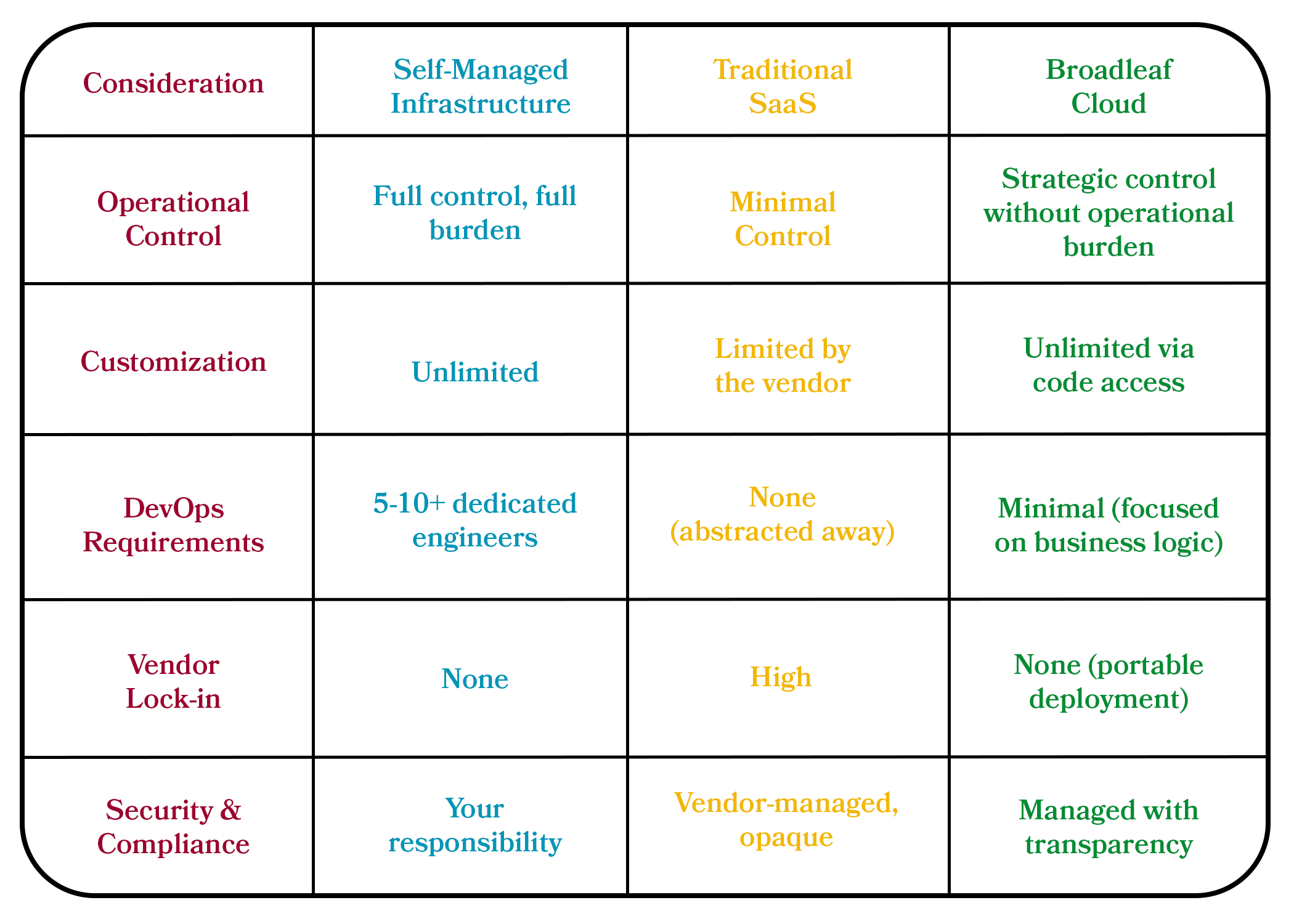

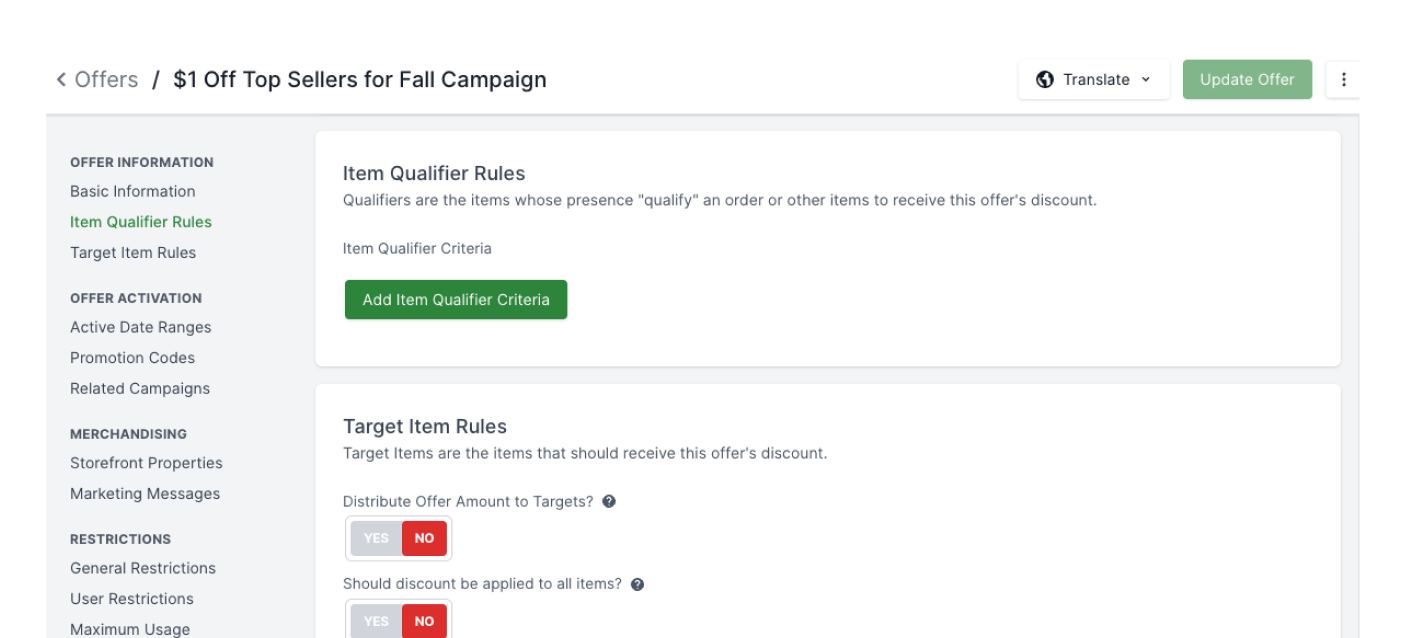

What’s the alternative? Let’s talk.